The search

for the highest road on earth

"Near the Ship-la we crossed

the border line of Tibet and India. Here, for the last time, we were at an altitude

of 16,300 feet. I remained long, gazing toward Tibet, the land of my victories

and my sorrows, the inhospitable land where both man and Nature create obstacles

for the traveller, and from whose dizzying heights the traveller returns with

a whole world of unforgettable, precious memories, in spite of the difficulties."

(Sven Hedin, when leaving Tibet for

the last time in 1908)

Photos from the trip - not

really ready yet...

I did two trip in Tibet in 2004. This, the second trip - august

to november - was a 4604 km adventurous bicycle odyssey with American Jeff Garnand

on roads through northeast and west-Tibet which included climbing a 6189 meters

mountain before going off-road 470 km into Tibet's uninhabited Chang Tang without

seeing people for 14 days. No doubt my best Tibet trip.

Interconnected

shallow lakes turn up on our right hand while we cycle gasping into the cold

mountain mist. We don't understand it, Djuma La, as the Tibetan nomads we camped

beside yesterday labelled the forthcoming pass, must be visible soon, but we

see nothing. We are cycling at 5300 meters altitude and the previous two days

climbed a 6189 meters (unclimbed?) peak in the Gandise range and cycled over

a well-maintained 5535 meters road pass we had never heard about before,one

of the highest road passes on earth. What is going on?

Interconnected

shallow lakes turn up on our right hand while we cycle gasping into the cold

mountain mist. We don't understand it, Djuma La, as the Tibetan nomads we camped

beside yesterday labelled the forthcoming pass, must be visible soon, but we

see nothing. We are cycling at 5300 meters altitude and the previous two days

climbed a 6189 meters (unclimbed?) peak in the Gandise range and cycled over

a well-maintained 5535 meters road pass we had never heard about before,one

of the highest road passes on earth. What is going on?

After last winter’s 3047km solo bike trip through Tibet, I somehow felt eager

to come back to Tibet soon again. I got in contact with American Jeff Garnard

whom I met cycling in Pakistani Kashmir in ‘99 when India and Pakistan were

on the verge of war. Jeff is an adventurer by heart and quit his extremely well-paid

job in IT and left his girlfriend behind to make probably the longest ever Tibet

trip by bike: a figure of eight route across the whole Tibetan plateau. Jeff's

plan is not just hot air - in ‘99 he cycled across the whole of Tibet in just

2 ½ months. I'm not that ambitious and before departure our joint cycling

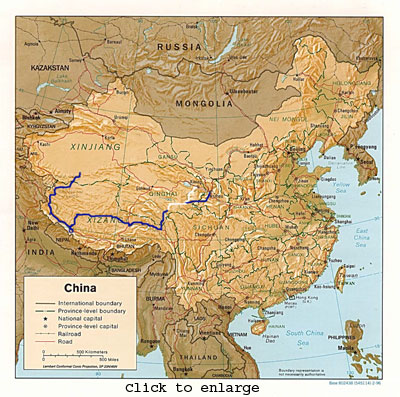

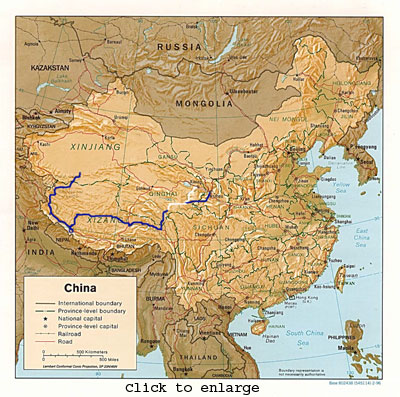

plan became starting out from Lanzhou in the Chinese province of Gansu in order

to cycle across the Tibetan plateau together. Jeff arrived in Lanzhou by train

from Beijing while I flew in from Beijing on the 7th August, arriving in China

a few days after Jeff.

We only enjoyed a day in this key point on the old Silk Road before starting

cycling southeast with the idea of crossing into Qinghai province. The surrounding

hills outside Lanzhou were a dry barren sandy experience while the temperature

midday reached well over 30 degrees, certainly not my favourite environment

for cycling. Worst of all, though, were the trucks transporting bees for pollinating

crops in the surrounding fields. For some reason they couldn’t stay away from

me. On one occasion while about thirty bees were around me, one bee stung me

next to my eye, causing the rest of the devils to try to follow his example.

Here I learned that I run faster than I cycle. Those days with the bees were

really a torment! The landscape slowly changed character into wide-open green

lush valleys where nomads on motorbikes were herding their sheep and yaks. We

began cycling on the smallest roads we could find on my Chinese maps, roads

which became extremely muddy and unpaved before crossing into Qinghai province.

Later we reached the Yellow river gorge and climbed a steep 4000m pass after

crossing the river and felt satisfied with our progress till then. As we were

about to start out the next day, I discovered a huge crack in my rear rim. It

was like being hit by a hammer, but somehow I felt very lucky - had the rim

failed while cycling down a deep gorge the day before toward the yellow river

at 50+ km/h it could have been end of my Tibet trips. It turned out the crack

came from my last winter tour, the whole inner double wall was cracked nearly

all the way around. I have never heard of such damage before. I took a chance

and cycled 56km with Jeff to a county capital where I grabbed a bus the next

morning to Xining, capital of the Qinghai province. The 500+ km trip took more

than 12 hours before I found a hotel in the evening. Before leaving Jeff, we

agreed to meet some 600 km later on our planned route in a town called Yushu.

Finding quality spare parts for a bike can be quite a problem in China. Luckily,

I have a really good friend in Siegfried Verheijke, Belgium Trade Commissioner

in Beijing (we set a Guinness record for altitude cycling together). When emailing

him, he instantly set heaven and earth on fire to make sure a wheel set was

sent express from Beijing to Xining. I received the wheel set and was as wild

as a lion in a cage to get back on the road again after being among backpackers

for three days. I simply don't share their concept of travelling. My destination

is the road between their highlights - my destination is the raw, long exhausting

hauls on dirt roads which drain all mental and physical strength. I somehow

belong to the mountains, the vast open plains at high altitude which to me represent

the ultimate freedom; no obligations, no limits, only pure freedom.

The 1200km detour was crowned with a 400km nightmare minivan trip before reaching

Yushu. The minivan of course got a puncture on the back left tyre and the spare

tyre fared no better. We were supposed to get assistance from Yushu but nothing

happened, so the driver tried to drive with a flat tyre. The car coming with

a spare tyre expected to see a stopped minivan and drove past us, to our driver's

extreme frustration, but finally came back and found us. Then 160 km of road

construction before we reached Yushu. It was 3am by the time, completely wasted,

I got into a truck guesthouse room in Yushu. I met Jeff the next day and spend

most of the day shopping and emailing in an internet café where a middle-aged

monk was playing CounterStrike – a shot-them-up-game. The next day we resumed

our bike trip out of Yushu together. Here, another tremendous shock hit. We

were cycling side by side just outside town when a blue Dong Feng truck overtook

us at slow speed. A yak-ox suddenly jumped out in front of the truck from the

left side of the road. The truck could not avoid the yak and hit it front on,

throwing the animal several metres through the air. Then the truck swayed to

the left at slow speed, broke through a barrier and fell three vertical meters

into a riverbed and landed on its side. Jeff and I threw our bikes down by the

road and ran over. A girl was already out of the truck when we got there, washing

her bloody face in the river. Two men also came out of the truck, looking little

better. A crowd quickly assembled around the place, but no one tried to help

in any way. Jeff and I were shocked again when no one even offered to drive

the wounded back to town and they had to walk back. One of the downsides of

China: few people will help others in emergencies. A few days later, we camped

next to a Chorchen – a religious tower - high up a hill. In the evening an immense

thunder system moved in and lightning hit frightening near us while our tents

were fluttering in the strong wind. No doubt, we were both very scared, but

the thunder calmed down, as we were about to leave our tents for lower grounds.

In this area we began entering a really mountainous area and plunged into official

Tibet after crossing an easy pass. Here we nervously approached a white checkpoint

building with a reddish Chinese flag flapping above. Luckily, the guards just

smiled and waved to us from the building - we were now in Tibet without problems.

The 1200km detour was crowned with a 400km nightmare minivan trip before reaching

Yushu. The minivan of course got a puncture on the back left tyre and the spare

tyre fared no better. We were supposed to get assistance from Yushu but nothing

happened, so the driver tried to drive with a flat tyre. The car coming with

a spare tyre expected to see a stopped minivan and drove past us, to our driver's

extreme frustration, but finally came back and found us. Then 160 km of road

construction before we reached Yushu. It was 3am by the time, completely wasted,

I got into a truck guesthouse room in Yushu. I met Jeff the next day and spend

most of the day shopping and emailing in an internet café where a middle-aged

monk was playing CounterStrike – a shot-them-up-game. The next day we resumed

our bike trip out of Yushu together. Here, another tremendous shock hit. We

were cycling side by side just outside town when a blue Dong Feng truck overtook

us at slow speed. A yak-ox suddenly jumped out in front of the truck from the

left side of the road. The truck could not avoid the yak and hit it front on,

throwing the animal several metres through the air. Then the truck swayed to

the left at slow speed, broke through a barrier and fell three vertical meters

into a riverbed and landed on its side. Jeff and I threw our bikes down by the

road and ran over. A girl was already out of the truck when we got there, washing

her bloody face in the river. Two men also came out of the truck, looking little

better. A crowd quickly assembled around the place, but no one tried to help

in any way. Jeff and I were shocked again when no one even offered to drive

the wounded back to town and they had to walk back. One of the downsides of

China: few people will help others in emergencies. A few days later, we camped

next to a Chorchen – a religious tower - high up a hill. In the evening an immense

thunder system moved in and lightning hit frightening near us while our tents

were fluttering in the strong wind. No doubt, we were both very scared, but

the thunder calmed down, as we were about to leave our tents for lower grounds.

In this area we began entering a really mountainous area and plunged into official

Tibet after crossing an easy pass. Here we nervously approached a white checkpoint

building with a reddish Chinese flag flapping above. Luckily, the guards just

smiled and waved to us from the building - we were now in Tibet without problems.

The next days were spent climbing up and down in the hilly terrain with rain

most nights. Climbing passes became daily events. We both managed to get food

poisoning on different occasions in this area, throwing up half the night and

struggling through the next day of cycling. After 1800 km of cycling (2400 km

for Jeff) we finally reached Nagqu, a major town with approximately 100,000

inhabitants. We had been talking about this place as a midway goal, joking that

the streets would be paved with gold there (we hoped at least the food would

be better). Completely worn down, I took a three-day rest here last winter after

extreme headwinds during the day and temperatures down to around -35°C at

night. Our stay here at 4200 meters lasted only one day and included our first

bath since Yushu more than 14 days before. We left Nagqu and cycled 40 km north

on the paved Golmud highway along the railroad under construction to Lhasa and

then turned off a shortcut to the northern route leading to western Tibet. This

was the beginning of a non-existent road, trucks having formed their own tracks

through the wide sandy valleys. Sometimes the main track divided into 15 smaller

tracks. Here we began seeing wildlife on a large scale: Chirus (Tibetan antelopes)

fleeing upon seeing us while Kiangs (Tibetan asses) curiously observed us riding

by. Cycling around the enormous salt lakes - one more than 100km long - was

a mental blessing and we camped next to the shores whenever we could. Strangely,

we never discovered at what point we actually reached the northern route from

the shortcut due to the track confusion, but it happened after about 260 km.

Here we tried to adjust our cycling after the location of the Hui (Muslim Han-Chinese)

restaurants around 80 km from each other, which were often just a tent. That

food was a blessing - homemade noodle soup with vegetables and bread. The Tibetan

teahouses offer at best just instant noodle soup or Tsampa, barley flour added

with butter tea. After 9 days of cycling from Nagqu, we reached a small town

called Nima, at 4400 meters altitude and about 550 km from Nagqu. This town

of around 5000 people serves as county capital for an area lager than 150,000

km² - more than three times the size of Denmark. A 27 year-old Chinese

construction engineer we met here was extremely helpful, lending us his laptop

for emailing since there were no internet cafés in town. He had stayed

here for three years co-leading a $10 million town centre construction programme.

But most interesting was the fact that he had a wolf cub as a pet, which he

found in the Chang Tang nature preserve to the north of town. It was locked

up in the courtyard of the town’s army weapons depot to protect it from the

Tibetans in town, who had attacked it once and wounded its hind leg. Tibetan

nomads hate wolves because they attack livestock. It was quite cute and I ended

up playing with this bundle of fur for half an hour. Wind harassed us as we

continued the 350 km toward Gerze on the northern route. Our average speed fell

to 6-8 km per hour when the headwind intensified to near storm force, draining

all physical and mental energy. Searching for a place to eat we ran into an

open goldmine run by the Tibetan local government. Some of the gold diggers

invited us into their camp and insisted we should eat there. They told us that

the annual production of gold was between 600 and 700kg at this site. I am quite

interested in the past exploration of western Tibet and their information that

it was an Englishman who discovered the place 100 years ago was extremely interesting

to me. On our departure they stocked us up with Chinese bread called manto and

wished us good luck. Gerze town was much bigger than Nima, not exactly corresponding

with what the construction engineer had told us. If things go as I hope, I shall

go to this town next summer to make a solo crossing of northern Tibet's Chang

Tang nature preserve, a 1000 km bike trip in uninhabited surroundings, a trip

which will take at least 45 days; more than one month in absolute solitude.

This represents the ultimate Tibet bike trip to me.

We found a bad $8 per person room and hung around town for one day before continuing.

We would like to have rested longer but our visa situation began to worry us.

We both had three-month Chinese visas and we were both 1 ½ months into

our trip. The question was; would it be possible to extend them in the prefecture

capital in western Tibet, Ali? If not, it meant we would have to shorten the

trip. We cycled on and reached Yanhu, a small busy town full of small shops

and restaurants situated just next to a large salt lake (yanhu means salt lake).

Outside town to the west was a small compact campsite crowded with Tibetan pilgrims

and old blue Dong Feng trucks parked nearby. Undoubtedly their destination was

Mt Kailash, south of the Gangdise/Transhimalaya mountain range we were now in

front of. Mt Kailash is the centre of the universe in Tibetan Buddhism and thousands

of pilgrims go there every year. We continued south the next day into the Transhimalaya

mountain range in order to reach a small settlement called Yagra. To our surprise

the road, which according to all our maps should follow a river valley up to

a lake next to the settlement, instead led over a 5290m pass, our highest point

until now. We descended down to Yagra the next day and discovered a much bigger

settlement than expected with shopping tents in lines at the north end of the

place. I cursed myself for buying supplies in Gerze for a 12 days off-road crossing

of Transhimalaya - everything we needed was here. A Tibetan in town gave us

some precise road information and we started out the next day to find a way

over the Transhimalaya to the Yalung valley on the south side. To our astonishment

the road led us into a side valley. Looking at my 1:500,000 Tactical Pilot Charts,

we realized a major road pass must be in front - surely higher than 5400m -

among the highest on earth. The official highest road pass is in India and the

altitude is claimed to be above 5600 meters, but cyclists riding there with

GPS have found it to be only around 5450 meters. The excitement gets a grip

on us - what is awaiting us? We cycle up a well kept road beside a small stream

and in the evening come to a point where we suddenly see a towering peak in

front of us, according to our maps 6180m high. We are completely flabbergasted

and agree to attempt to climb it the next day. While riding higher up the road

to make a base camp for the climb we suddenly see the wall on our left leading

up to the road pass as well, with switchback bends all the way to the top. Jeff

is in a state of ecstasy - he loves passes and he now sees what may be the highest

road pass on earth - it must be higher than 5500 meters high!

The next day we leave base camp early and after traversing 8-10 km over a small

hill, we take a rest on a pass saddle before we begin the actual climb. We ascend

quite fast, more than 300 meters/hour and in just three hours from the base

camp at 5300 meters we find ourselves on the top of the peak at 6189 meters

altitude. The wind from the south is intense and we seek shelter on the north

side while admiring the Transhimalayan peaks around us in the nearly cloud-free

sky. We don't find any sign of people having been up here before and build a

small chorchen of stones and walk down again, exhausted. The next day, we ascend

the 5535 meters road pass and I cannot help trying to lift my bike over my head

while Jeff films the event with my video camera, but it is too heavy. We are

both certain that we are the first to cycle this pass. We cycle down from the

pass next to a river and end up camping by a nomad tent in an open windy valley.

In the evening they treat us to butter tea and tsampa and tell us about their

families and the area. They also try to tell us about the pass ahead in a manner,

which makes us worry a bit. Next morning they give us enough tsampa and rice

for several days. Had we known what was waiting, we might have hesitated a bit.

We ended up cycling more than 35 km above 5300 meters altitude, peaking at a

5428 meters pass at the end of a 15 km long lake where we camped before riding

over the pass the following morning. Riding along the lake, we cycled through

a small snowstorm and could easily have gotten into serious problems had it

not stopped snowing.

After descending the Transhimalaya, we cycled around Turkish-blue Lake Manasarovar,

a roundtrip of 100km, a two-day trip where we stayed overnight for free at a

monastery complex after three monks had grabbed our bikes and cycled around

on them for an hour. Then came the trip to Mt Kailash. We cycled to Darchen,

the town lying at the foot of the mountain, paid $50 each for a permit and a

fine for being in the area, stored our bikes in the home of a friendly bank

employee we met in town and began the trek. We had really bad backpacks, Jeff

was worst off with a bag with really thin straps. Surely we would end up with

shoulder pains! We managed to walk some 15 km of the total 53 km during the

rest of the day on the west side of Mt Kailash during our clockwise kora around

the mountain. We spent the night in Jeff's tent and watched devoted pilgrims

passing us in the morning light while packing. We came across a group of young

pilgrims on a one-day kora while ascending toward the Dromo La pass on the north

side of Kailash. We followed them for some time and while filming them, they

urged me to follow them through a small tunnel system among some rocks. I got

part of the way but they soon realised that my 185cm height would not be able

to make the whole way through. Up on top of the pass at 5600 meters altitude

were the traditional prayer flags fluttering loudly in the wind and Tibetans

celebrating the ascent by throwing dry Tsampa into the air as a religious offering.

We began the descent; a long haul to Darchen waited. My feet were pretty swollen,

the shoulder now hurt a lot, forcing me to bend forward while walking - the

fun was gone. Jeff was in front as usual, just as when cycling, daylight vanished

slowly and it became cold. Not until darkness approached did I arrive back in

town, completely beaten up like last time (I first did this kora three years

ago during a bike trip across west Tibet). I met Jeff again in the banker’s

house where the banker’s grandparents were singing religious songs while he

was out having a drink in town. Jeff sat staring apathetically into the air

when I arrived. Next day, we met an Indian guy who had walked around Kailash

155 times - more than 8000km! 117 times should be enough to achieve nirvana,

but nothing happened to him after the 117th trip; instead he got a vision to

continue his koras around Kailash. I guess he must have gotten a bit disappointed.

We had a long talk with him and he showed us a small booklet presenting a plan

for 100,000 Indian pilgrims coming to Kailash every year. Some of it sounded

quite appealing, other parts were quite far from reality – e.g. helicopter service

at 4600 meters altitude…

We jumped on our bikes and cycled west through the wide Gar river valley, with

7727 meters high Mt Gula Mandatta marking the Himalaya range to the south, next

to West Nepal. Later while cycling in the valley, we had to cycle in a small

blizzard making cycling less fun as temperatures plunged below -2°C at night.

After a couple of days of cycling, we ate at a Chinese restaurant next to an

army base. Unfortunately, this led to food poisoning again and I had to spend

half the night waiting for the inevitable throwing-up session. This was a great

setback for our plans to try to get over what should be the highest road pass

on earth at 5900 meters, the road not having been in use for a long period.

It had to be attempted, so after half a rest day we went into a narrow valley

south of the road, throwing our faith into a map from a guidebook on Tibet from

1994 where the pass is shown precisely. After 10 km of cycling on a really good

road, we ran into a nomad who said there was no road over the Bogo La pass,

that we would have to walk - and most frighteningly he pointed at a vertical

wall to illustrate the difficulties. Here our hopes fainted, but even though

I was not feeling good, we agreed we had to go further on the good road to see

with our own eyes what was actually up there. The ride further up through the

narrowing valley becoming a gorge was a cobweb of small river crossings, dark

cloud formations moving fast above our heads, giving no indication of whether

bad weather was coming in for real or not. Finally we reached an open valley

at 5100 meters altitude; evidently the nomads had moved down through the gorge

to avoid the cold winter here. To our disappointment, the road disappeared into

nothing at 5200 meters - the Bogo La road pass is a ghost - but obviously this

valley has served as a pilgrim route over Bogo La as big piles of mani stones

laying along a no-longer existent trail going up the pass. We looked carefully

at my TPC map and the 7 contour lines marking 500 feet intervals within 5km

convinced us that it would be hazardous to go over the snowy pass if there was

not some kind of road on the other side. After a -22° C camp here, we descended

to the main road again the next day. Our goal was now Ali, the biggest town

in western Tibet. We have not had much rest during the last two months of cycling

and our minds now focused totally on this "paradise". We cycled right

into the Chinese attempt to let far western China take part in the country’s

massive annual growth, which is currently restricted mainly to the coastal regions

in China: we found an 85km asphalt road leading directly to Ali. Such a difference,

all the stony, sandy washboard we have suffered is replaced here with a superb

paved road. We were ecstatic - normally we prefer gravel roads, but the trip

has taken its toll on us - I have lost more than 10kg and Jeff over 5 kg - we

need rest! We cycled all the way to Ali the same day and have now been staying

here for three days enjoying food and showers like never before. We needed that

after 3642km of cycling (4200 km for Jeff) and climbing more than 33 vertical

kilometres by bike. Fortunately, the police in Ali turned out to be more cooperative

than we had been told and we got a one-month extension of our existing visas,

enough to get us to the Muslim Xinjing province north of the Tibetan plateau.

The trip together is far from finished - on the contrary! It's now that the

serious part begins! We will head up to northwest Tibet, stocked up with more

than three weeks’ food supplies, take a deep breath and then head east into

the western part of the uninhabited Chang Tang nature preserve, second largest

on earth after ice-capped northeast Greenland. Cycling here is mostly impossible

due to soft terrain above the permafrost layer. We'll have to push the bikes

all day and only travel 25km at best in this high-altitude environment mainly

above 5000 meters. Deep into Chang Tang we turn north in order to cross a fault

formation in the Kunlun mountain range leading down to the Taklamakan desert.

We will unfortunately be in Chang Tang in November when wind and temperature

conditions worsen dramatically - frequent strong storms will occur and the temperature

will plunge far below -30° C at night. There is no one to help us out if

something goes wrong in this place, which field biologist Dr. George Schaller

has described as being among the most inaccessible places on earth. This is

the way we want to do it - complete an expedition into Chang Tang on the same

terms as the early Tibet explorers. Coming down from the plateau again after

crossing 500km through Chang Tang and cycling 4000km on the plateau, Jeff will

cycle east to finish his figure of eight trip through southeast Tibet, while

I consider crossing the Taklamakan desert on a 600km oil highway. However, we

will both have to get visa extensions from the local police in a Taklamakan

oasis town called Hotan, but according to our information this should be easier

than in Ali. Sorry, this mail became a bit long, but I got caught up in it…

___________________________

deep into uninhabited Chang Tang , following

a migration route for Tibetan antelopes

ascended over an easy 5141 meters pass and

entered the fault formation separating the West and East Kunlun range, also

birthground to Selektuz river. Then descended down this nearly 100 km. long

and sometimes narrow gorge until reaching Karasai village at 2960 meters at

the edge of Taklamakan desert.

Interconnected

shallow lakes turn up on our right hand while we cycle gasping into the cold

mountain mist. We don't understand it, Djuma La, as the Tibetan nomads we camped

beside yesterday labelled the forthcoming pass, must be visible soon, but we

see nothing. We are cycling at 5300 meters altitude and the previous two days

climbed a 6189 meters (unclimbed?) peak in the Gandise range and cycled over

a well-maintained 5535 meters road pass we had never heard about before,one

of the highest road passes on earth. What is going on?

Interconnected

shallow lakes turn up on our right hand while we cycle gasping into the cold

mountain mist. We don't understand it, Djuma La, as the Tibetan nomads we camped

beside yesterday labelled the forthcoming pass, must be visible soon, but we

see nothing. We are cycling at 5300 meters altitude and the previous two days

climbed a 6189 meters (unclimbed?) peak in the Gandise range and cycled over

a well-maintained 5535 meters road pass we had never heard about before,one

of the highest road passes on earth. What is going on?  The 1200km detour was crowned with a 400km nightmare minivan trip before reaching

Yushu. The minivan of course got a puncture on the back left tyre and the spare

tyre fared no better. We were supposed to get assistance from Yushu but nothing

happened, so the driver tried to drive with a flat tyre. The car coming with

a spare tyre expected to see a stopped minivan and drove past us, to our driver's

extreme frustration, but finally came back and found us. Then 160 km of road

construction before we reached Yushu. It was 3am by the time, completely wasted,

I got into a truck guesthouse room in Yushu. I met Jeff the next day and spend

most of the day shopping and emailing in an internet café where a middle-aged

monk was playing CounterStrike – a shot-them-up-game. The next day we resumed

our bike trip out of Yushu together. Here, another tremendous shock hit. We

were cycling side by side just outside town when a blue Dong Feng truck overtook

us at slow speed. A yak-ox suddenly jumped out in front of the truck from the

left side of the road. The truck could not avoid the yak and hit it front on,

throwing the animal several metres through the air. Then the truck swayed to

the left at slow speed, broke through a barrier and fell three vertical meters

into a riverbed and landed on its side. Jeff and I threw our bikes down by the

road and ran over. A girl was already out of the truck when we got there, washing

her bloody face in the river. Two men also came out of the truck, looking little

better. A crowd quickly assembled around the place, but no one tried to help

in any way. Jeff and I were shocked again when no one even offered to drive

the wounded back to town and they had to walk back. One of the downsides of

China: few people will help others in emergencies. A few days later, we camped

next to a Chorchen – a religious tower - high up a hill. In the evening an immense

thunder system moved in and lightning hit frightening near us while our tents

were fluttering in the strong wind. No doubt, we were both very scared, but

the thunder calmed down, as we were about to leave our tents for lower grounds.

In this area we began entering a really mountainous area and plunged into official

Tibet after crossing an easy pass. Here we nervously approached a white checkpoint

building with a reddish Chinese flag flapping above. Luckily, the guards just

smiled and waved to us from the building - we were now in Tibet without problems.

The 1200km detour was crowned with a 400km nightmare minivan trip before reaching

Yushu. The minivan of course got a puncture on the back left tyre and the spare

tyre fared no better. We were supposed to get assistance from Yushu but nothing

happened, so the driver tried to drive with a flat tyre. The car coming with

a spare tyre expected to see a stopped minivan and drove past us, to our driver's

extreme frustration, but finally came back and found us. Then 160 km of road

construction before we reached Yushu. It was 3am by the time, completely wasted,

I got into a truck guesthouse room in Yushu. I met Jeff the next day and spend

most of the day shopping and emailing in an internet café where a middle-aged

monk was playing CounterStrike – a shot-them-up-game. The next day we resumed

our bike trip out of Yushu together. Here, another tremendous shock hit. We

were cycling side by side just outside town when a blue Dong Feng truck overtook

us at slow speed. A yak-ox suddenly jumped out in front of the truck from the

left side of the road. The truck could not avoid the yak and hit it front on,

throwing the animal several metres through the air. Then the truck swayed to

the left at slow speed, broke through a barrier and fell three vertical meters

into a riverbed and landed on its side. Jeff and I threw our bikes down by the

road and ran over. A girl was already out of the truck when we got there, washing

her bloody face in the river. Two men also came out of the truck, looking little

better. A crowd quickly assembled around the place, but no one tried to help

in any way. Jeff and I were shocked again when no one even offered to drive

the wounded back to town and they had to walk back. One of the downsides of

China: few people will help others in emergencies. A few days later, we camped

next to a Chorchen – a religious tower - high up a hill. In the evening an immense

thunder system moved in and lightning hit frightening near us while our tents

were fluttering in the strong wind. No doubt, we were both very scared, but

the thunder calmed down, as we were about to leave our tents for lower grounds.

In this area we began entering a really mountainous area and plunged into official

Tibet after crossing an easy pass. Here we nervously approached a white checkpoint

building with a reddish Chinese flag flapping above. Luckily, the guards just

smiled and waved to us from the building - we were now in Tibet without problems.